Slings and Arrows and Bondage

The cinematic James Bond turns 52 this year, and is both a distinguished relic and as vital as the year he was birthed. The literary James Bond turns 61, and inhabits a perculiar realm as both precursor and shadow to his cinematic counterpart. Inspired by Film Critic Hulk’s recent series on Bond and invigorated by our recent discussions of Batman 89, Anthony and I decided to revisit ground zero for Bond on film, Dr. No.

BEN: Looking at the Bond films and their literary sources side by side can be a head-scratching, hair-pulling exercise. These aren’t like other book-to-film series, like Harry Potter, where the films follow the same order as the source texts and are relatively faithful adaptations (albeit with the usual concessions that come with adaptation). No, the Bond films follow a completely different order to the Bond books, and vary wildly from reasonably faithful translations to similar-in-name-only.

Dr. No is a case in point. The first of the Bond films and the prototype for all that followed, it’s actually based on the sixth Bond book. If you watched the James Bond films in the order of the books that spawned them, you’d begin with Daniel Craig’s card-playing blunt instrument in Casino Royale, then segue to Roger Moore jumping over alligators in Live & Let Die and getting into space battles in Moonraker, then segue to post-toupee Connery in Diamonds are Forever and then pre-toupee Connery in From Russia with Love before finally getting to Dr. No. When you finally got there, you’d probably wonder why the gun barrel opening has a weird music box quality and the opening credits feature ‘Three Blind Mice’. It’d be akin to watching Star Wars and seeing the opening text scroll horizontally rather than vertically.

Similarly, if you tried reading the books in the order of the films, starting with Dr. No, you’d miss out on all the stuff from the previous novels that culminated in the Bond of Dr. No, and you’d probably be underwhelmed too. After all, when we meet Bond around 10 minutes into the movie version of Dr. No, it’s this iconic moment. When we get to Bond twelve pages into the book Dr. No, Fleming writes “James Bond came through the door and shut it behind him. He walked over to the chair across the desk from M and sat down”. Not exactly mythic, and certainly not a patch on our REAL introduction to Bond, this vivid, muscular passage from Casino Royale published five years earlier: “James Bond suddenly knew that he was tired. He always knew when his body or his mind had had enough and he always acted on the knowledge. This helped him to avoid staleness and the sensual bluntness that breeds mistakes”. The gist is, you can’t really look at the Bond films and books side by side. Where, say, Potter in print and film inhabit the same narrative world, Bond in print and film inhabit completely different, alternate realities. However, it’s fascinating and illuminating to look at how the films riffed on their sources, which can tell us a lot about those particular moments both in Bondage and broader popular culture.

Anthony, I think you’re a bigger admirer of the books than I am. Why do they ring your bell and what does Dr. No do for you?

ANTHONY: Well, my admiration for the Bond books is not a standalone affair. I bumped into them as a teenager after growing up on the films. With the excesses and indulgences of Diamonds are Forever and Moonraker films as a reference point, Fleming’s thrillers seemed smarter and far more dangerous. It was a similar experience to watching Friday the 13th and Prom Night before discovering John Carpenter’s original slasher Halloween. The original material is so much stronger after seeing the dregs of the adaptations and imitations, and how Bond plays out in both mediums will likely guide my comments for the remainder of these chats.

Still, the reasons why I Iove the Bond books are because of how they better represent elements I first found in the films. I already loved those things about Bond, but the books presented those qualities with a straight face and something approximating vivid realism. I’d argue there’s something close to a narrative integrity in the books that rarely surfaces in the films. Case in point, Ben, you mention that the Bond films were shot in a different order from the books and often do not stand side-by-side comparisons. As a reader of the books, I’ve seen something of a narrative unfold over the novels. As the films are shot out of order, sequential elements of plot and character are absent. For instance, Strangways and Quarrel are significant parts of the earlier book Live & Let Die. They are established as characters that are tragically killed in Dr. No when Bond returns to Jamaica. In fact, Strangways death functions as the inciting incident in Dr. No (the three blind mice scene) and comes as something of a shock as you’ve known the character from Live & Let Die. The film Dr. No lacks those characters as an anchor and reference point and also a sense of the book’s dramatic weight. As the films don’t follow the order of the books, and must ignore the threads of narrative consequence that Fleming wove through his, they are drawn further away from a credible sense of reality. Bond even has something like a character arc, or at least an entangled involvement in escalating events, in the books. I’ll rant more about this later.

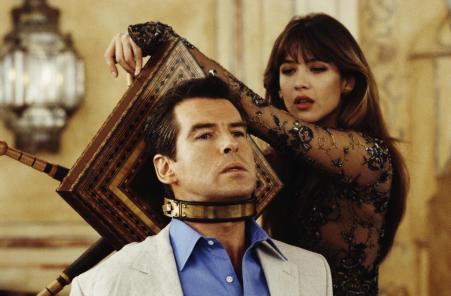

As a film within the franchise, Dr. No can seem a little like a curiosity. We see each of these recognizable elements, the gun barrel opening, the opening titles displayed on the bodies of dancing women, the opening meeting with M, but they seem strangely spartan. As you mentioned, the opening to Dr. No might seem odd to someone who knows the later entries in the series. As a spy film, isolated from comparisons to other books or films, Dr. No doesn’t do a lot for me. Sure, Ursula Andress is stunning and Dr. No himself is fun and villainous. The action beats are fine for the film’s context. I do quite enjoy seeing Connery settling into the character for the first time. His sense of charisma is a little more off the hook here than it was in future, less Bond by numbers and more a young actor striving to nail a part. Connery’s a little more laconic and rough around the edges. I like it, though again, only as a counterpoint to the later films.

Then there is the issue of the Bond Women. First, when we speak of enjoying the Bond films and books, it is in a very particularly context. This context is one in which we acknowledge the excitement and fun of this property alongside its objectionable sexism, racism, homophobia and violence. Some of that can be ignored, some can be appreciated ironically (which the films certainly do from time to time) and some can be enjoyed in a balanced sense of indulgence. Some of it cannot be forgiven though. Film Critic Hulk discussed this thoroughly in his own aforementioned Bond spiel. Of course, many might enjoy these elements of the property in an entirely unhelpful manner, which I suspect is a big part of the series’ appeal as well. It is in light of this questionable indulgence, that we can discuss Bond women as an undeniable appeal of the series as well as its weakest point.

Ben, shall we discuss Dr No’s Bond woman, Honey Rider?

BEN: Honey Rider’s an interesting character. The film character is rightly iconic, mainly on account of her striking entrance and ensemble as well as for being the first major Bond girl, and while I don’t think Ursula Andress’s performance quite rises to the iconography – especially compared to Daniela Bianchi, Honor Blackman, and Luciana Paluzzi over the next few films – all the other ingredients gel nicely. The character in the book has a lot more backstory and depth, but certain notes ring false, e.g. when Bond and Rider are imprisoned by Dr. No and she suddenly gets crazy horny and has to be chastised by Bond. That sort of patriarchal sexism is a recurring feature of the Bond books, as are somewhat racist sentiments – e.g. the Jamacian character Quarrel’s heavily accented “Gawd, cap’n! What’s dat fearful ting?” (p. 101) – and these features tend to age the books quite a bit. I don’t know enough about Ian Fleming’s personal life to conjecture whether these are fair reflections of his own attitudes, but I get the sense when reading the books that, like a lot of airport novelists with certain niches (e.g. Tom Clancy with the military, Michael Crichton with science, John Grisham with law) he wrote what he knew, meaning that while Fleming nailed his depiction of British intelligence and nailed his depiction of topics, people and places that interested him, sometimes he would be the stuffy British imperialist looking at something quizzically from the outside, and it would show.

Since you raise the questionable aspects of the Bond mythos and how they work today, I’ll digress briefly here to share an idea I’ve floated with a few people. I would love – LOVE – to see a Mad Men-style television adaptation of the Bond books, done in the order of their publication, with two books covered per season. When I read the books these days they really do feel like Mad Men: the period setting, the fetishizing of places and food and drinks and clothes, the everyday sexism and racism, and the long, long conversations. For example, looking at Dr. No, the three page discussion about guana, the one page monologue about Chinese Negroes, and Dr. No’s six pages of dialogue recounting his personal history would all stop a film dead, but in a longform television program could be really cool. It’d be a way of adapting those awkward elements of Fleming and presenting them as a time capsule while also weaving in some commentary, and it would also mean some of the weirder things we’ve never seen from the Bond books – e.g. The Spy Who Loved Me, in its original form, is a home invasion narrative set in an isolated hotel and narrated by its female caretaker – could be adapted. Anyhow, that’s my dream project of the moment. But I digress…

While I noted earlier the weird disjunctions between watching Dr. No as the first instalment of the film franchise and reading it as the sixth instalment in the book series, it’s actually a pretty straightforward piece of adaptation. The broad plot beats are fairly identical: Bond goes to Jamacia to investigate the death of agent Strangways, finds out Strangways was investigating the criminal activities of Dr. No, visits No’s island where he meets Honey Rider, gets imprisoned by No, eventually confronts and defeats his enemy, and makes sweet love to Rider at story’s end. The little differences are interesting – for instance, the scene where Bond confronts a tarantula in the film is a centipede in the book, the song that Honey Rider sings on making her entrance is different etc – and the usual embellishments and/or trims that come with the adaptation process are generally sound (i.e. no long conversations about guana). Having said that, I’m particularly disappointed that a scene in the book where Bond fights a kraken – REPEAT: BOND FIGHTS A KRAKEN – didn’t translate to film (Roger Moore does wrestle a giant snake in Moonraker, but that’s for a future post). Seriously, that scene is up there with the Garden of Death in the book You Only Live Twice when it comes to top things I want in the Bond films but haven’t seen yet (paging Mad Men producers, paging Mad Men producers…).

While the film doesn’t have a kraken, it has something even better: Sean Connery. Whilst some of Fleming’s more anachronistic attitudes to race and sex are prevalent in the film, and indeed the film series in general, Dr. No in some respects actually feels like a very modern film. In fact, it feels much more modern than many of the later films. This is partly due to director Terence Young’s clean, stripped down approach, i.e. there’s nothing in terms of gadgets or set pieces that dates the film, whereas, say, the jet pack Bond uses at the start of Thunderball is a great big red flag that we’re very much in the past. But what also makes it feel modern is Connery. The chauvinism Bond displays throughout is certainly of its era, but Connery gives a performance so charismatic and magnetic and cool that it really does transcend its era, the same way Harrison Ford’s work in Star Wars and Raiders of the Lost Ark or Clint Eastwood’s work in the Dollars trilogy remain electric and contemporary. There’s something about Connery, gender politics aside, that feels timeless, whereas each Bond actor that followed, while all absolutely brilliant in their own way, feel tethered to their time (hell, you can tell what day of the week George Lazenby was Bond). It sort of helps that Bond is surrounded by old dudes in these early films, e.g. Bernard Lee’s M, Desmond Llewelyn’s Q, and that Connery exited the series before he, like Roger Moore, grew old alongside them (though he pushed it a bit with Diamonds are Forever). Whatever the case, the fact remains that Dr. No, while relatively low fi in comparison to instalments that followed, benefits from this low fi approach and is really high in Bond wattage.

ANTHONY: Yeah, I’ve not even touched on the racism in the book of Dr. No (the ‘Chigroes’, Quarrel’s mannerisms, etc). Too be honest, it’s a very unpleasant blemish on the book and film. As for the sexism, Honey Rider is an interesting example of the difference between the films and books. Honey Rider is the first Bond woman of the film franchise and therefore quite historic. Her noted ascent from the ocean is a scene later referenced by Jinx in Die Another Day and by Bond himself in Casino Royale. She is, however, handled in a typically sexist fashion. She is generally objectified, patronised and exploited.

Rider in the books, named Honeychile, offers a little more complexity. She sports a broken nose and boyish buttocks. She is a victim of rape and tough as nails. She lives in the remains of a crumbling house and is something of a caretaker for her own wild menagerie. Bond is reluctant to sleep with her until he has killed Dr. No and later arranges relevant employment for her, foreseeing the temporary nature of their relationship. Fleming would expect his readers to see Honeychile as a vivid and strong woman (which she is) and Bond’s treatment of her as noble. While she is brilliant and tough and independent, she remains subjected and all too willing to fall into Bond’s arms like a schoolgirl. That is precisely how Bond women appear in Fleming’s texts, over and over. It’s still sexist, though a more naunced and complex sexism than the films often displayed. That is generally my perception of the gulf between prose and celluloid with this franchise…

Leave a comment